If you save a text file with non-english characters and wondered how the editor knows how to interpret it correctly, then this is for you.

The Unicode standard defines a set of rules that govern how text is encoded and stored as bytes, such that it can be read back preserving the information that was encoded. In this tutorial, we’ll particularly look at UTF-8.

In UTF-8, characters are given a number, also known as code point, and these code points are grouped into what we will call code blocks for simplicity. The code block determines to an extent, how many bytes will be used to store the data.

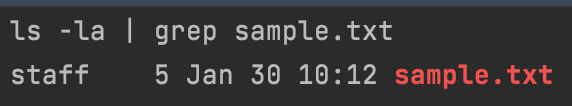

Now, let’s see what this means in practice. if we open a notepad and type in the word “hello”, save the file as a text file (“sample.txt”), and check the file size, we will see it’s 5 bytes which makes a little sense as there are only 5 characters:

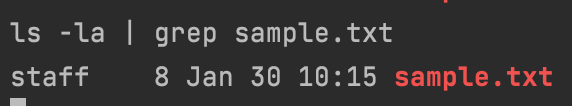

We see ‘5’ Just before Jan 30, which is the size of the file. Now, let’s add the Chinese character ‘不’ just after hello in our text file like this “hello不”. If we save that and check the file size again:

We see that our file size is now 8 bytes. But we only added a single Chinese character, why does that add 3 extra bytes instead of 1.

The answer to that is that our text file is UTF-8 encoded, so some characters need a single byte, while some others need more than one byte.

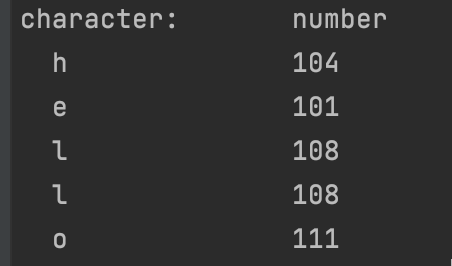

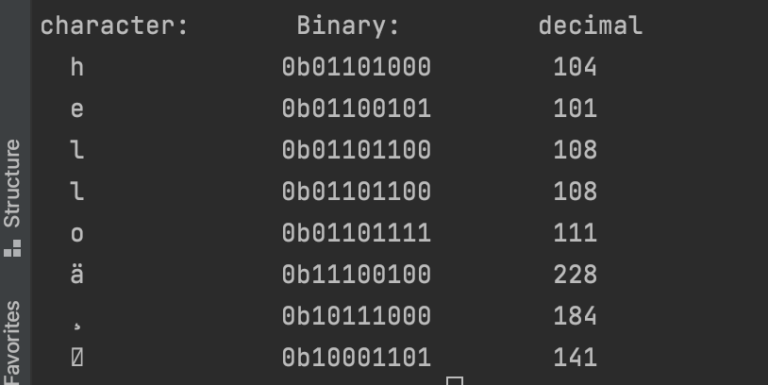

The English alphabet typically needs one byte or 8 bits to store every possible English character. We can see it here in this ASCII chart. ASCII is simply just some convention to map characters or symbols to a number. To make sense of the ASCII chart, let’s print out each character in our text file without the Chinese character. According to our chart, the characters “hello” should be 104, 101, 108, 108, 111. This simple rust code shows that:

let res = std::fs::read("sample.txt").unwrap();

println!("character:t number");

for elem in res {

println!(" {}tt {}",elem as char,&elem)

}

Which prints out :

Now, this makes sense, but what happens when we add our Chinese character ‘不’ in there:

We can see that everything after “hello” isn’t what we expected, the three numbers after “hello” i.e( 228, 184, 141 ) should have represented the Chinese Character ‘不’, but we’re seeing something else instead:

But our notepad has no problem interpreting those numbers to represent the Chinese Character, so it’s obvious that it’s doing something we’re not doing, or has some piece of information that enables it to properly translate those numbers into the Chinese character. we actually expected. To understand how this works, we’ll get a little more technical and look into the bit representation of these characters and more.

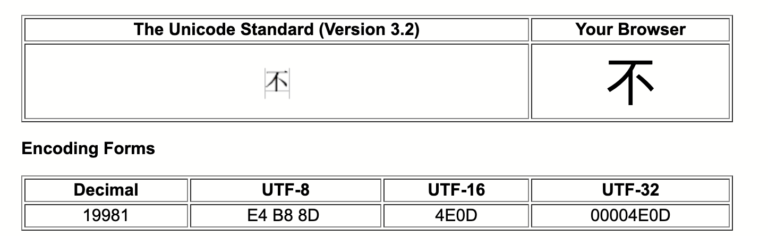

Remember when we said that every character has a code point (number) and belongs to a code block that defines how many bytes are used to store the character. Let’s see the code point for our Chinese Character ‘不’

One thing we can see is that the number/ code point given to this character is 19981, and the hex representation is 4E0D. Now in UTF-8, when we write the code point of a character, we write as U+, followed by its hex representation, so for our Chinese character, the code point is written as U+4E0D.

Here are the code blocks we have. To make our example simple, will summarise the code blocks, giving the range of values and how many bytes can be used to store their values:

Code Blocks <-> Bytes needed

| First Code Point | Last Code Point | Bytes needed | Exact Bits needed |

|---|---|---|---|

| U+0000 (0) | U+007F (127) | 1 | 7 |

| U+0080 (128) | U+07FF (2047) | 2 | 11 |

| U+0800 (2048) | U+FFFF (65535) | 3 | 16 |

| U+10000 (65536) | U+10FFFF (1114111) | 4 | 21 |

Now, we can see that our Chinese Character falls in the 3rd code block that needs 3 bytes to store its data. We will get to “Exact Bits needed” soon.

Before we go into how this character is encoded into bytes, let’s just see the binary as well as hex representation each character in our text file that contains the Chinese character:

This piece of rust code helps us:

println!("character: t Binary:t decimal t");

for elem in res {

println!(" {}\t\t{:#010b}t {}",elem as char,&elem,&elem)

}

Our output is:

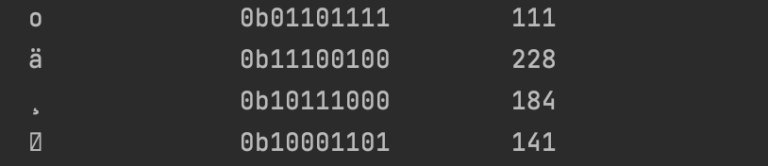

It’s worth noting that after the ‘o’ in “hello”, the Chinese character is stored as 3 bytes with numbers (228,184,141) and binary representation (excluding the ‘0b’):

11100100 10111000 10001101

Now, how did our text editor convert our Chinese character that had a number 19981 or a code point of U+4E0D into that binary format.

Our first guess will be to convert the number directly into binary, but we will get this 16-bit value:

01001110 00001101

Which doesn’t look like what was stored by our notepad. Also, we see that our data can fit into 16 bits, but the encoding says we must use 3 bytes due to the code block it belongs to. Then it’s obvious that the other 8 bits will store some other kind of data we don’t know about yet.

Think of UTF-8 encoding as some mechanism to pass metadata along with the actual data so that it can be interpreted correctly

Now, let’s see how these characters are encoded:

UTF-8 Encoding/Decoding

We will try to oversimplify this and make it very easy to understand.

Writing / Encoding:

Let’s see how our Chinese character ‘不’ is practically encoded. Remember that its code point is U+4E0D (decimal 19981) and from our Code block <-> bytes needed, we see that it falls in the block that needs 3 bytes, so we must use 3 bytes to store this information.

For simplicity, let’s think of our 3 bytes as 3 containers of 8 bits (1 byte) all with empty values. Will use ‘x’ to represent an empty bit, i.e, a bit yet to be filled with a 1 or 0.

3 Byte Container

| Container 1 | Container 2 | Container 3 |

|---|---|---|

| xxxxxxxx | xxxxxxxx | xxxxxxxx |

According to the UTF-8 Encoding spec, it says that because our character will be three bytes long, we must fill the leading bytes (left most bytes), which in our case is in container 1, with three 1s followed by a 0. i.e, begin with 1110 to signify that this byte belongs to a group of 3 bytes

So we’ll fill the first four empty bits, ‘x’ in our case, with three 1s and a 0. as explained by the spec. Because the encoding will be three bytes long, we have to do this.

Our container then looks like this.:

3 Byte Container

| Container 1 | Container 2 | Container 3 |

|---|---|---|

| 1110xxxx | xxxxxxxx | xxxxxxxx |

Now, the encoding spec also says that the leading (leftmost) bits of the next two bytes, which in our case is in container 2 and 3, should begin with 10. This signifies a continuation byte, i.e, this byte is not standalone and should not be interpreted as such, rather it is part of a previous sequence of bytes that should be combined and read as a single value. This is the most important thing to be aware of.

What this encoding says simply is that, when you see a byte that begins with 10, don’t just interpret it as a character, but instead treat it as a continuation of some byte sequence that needs to be read together at once. This was the mistake we made when reading the Chinese character, we were blindly reading each byte and trying to convert it into a character, not knowing that it was part of a contiguous byte sequence that resulted in a larger code point, number of character.

If we do this, our container should look like this:

3 Byte Container

| Container 1 | Container 2 | Container 3 |

|---|---|---|

| 1110xxxx | 10xxxxxx | 10xxxxxx |

Now, if you count how many empty slots denoted by ‘x’ we have left, we see that it’s 16, which as we saw in the previous section is the exact amount of bits we need to store our Chinese character with a code point of U+4E0D (19981) which is represented in binary as

01001110 00001101

Now, let’s fill those empty slots (‘x’) with our 16-bit code point starting from the left. Our container will then look like this:

3 Byte Container

| Container 1 | Container 2 | Container 3 |

|---|---|---|

| 11100100 | 10111000 | 10001101 |

With this, we’re done with our encoding. So our UTF-8 encoding for the code point U+4E0D is :

11100100 10111000 10001101

If we look at this number, we will see it is exactly the same binary representation of the last three bytes used to represent the Chinese character that we printed out (excluding the 0b):

Now, we can see that our notepad actually did UTF-8 encode the Chinese character, but our problem was we were incorrectly reading it programmatically.

Now that we’re confident that our text was correctly encoded, let’s see how to properly decode it.

P.S, We’ll call the extra 8 bits of data we added “metadata” as we’ll use them to interpret our data in the next section.

Here’s an excerpt from Wikipedia.

Reading/Decoding:

According to the UTF-8 spec, when reading bytes, we should be careful of how we interpret a contiguous stream of bytes, some should be interpreted individually, while some should be interpreted as a group.

Here’s an oversimplified summary of how to interpret a stream of bytes (8-bit sequence) in UTF-8:

- If a byte starts with the bit 0, then it’s a single byte data and rest of the bits can be interpreted or decoded as an individual code point or number or character in our case.

- If a byte starts with a sequence of 1s before a 0, the number of 1s it starts with, i.e, the numbers of 1s before the very first 0 tells the size of the group or nunber of bytes that should be collected and processed or decoded together. Everything else in this byte after the first 0 is part of the data itself.

In our example, we see that our Chinese character starts with:11100100which means that this byte is part of a group of 3 bytes that should be processed together, so the nth, n + 1 and n + 2 bytes together form the group that should be decoded together. - If a byte starts with 10, then it’s a continuation byte and is linked to the byte before it and every bit after the 10 or the first 0 is the data itself

Of course, this is an oversimplification, but let’s use these rules to decode our stream of text and hope we can get back “hello不”.

First, let’s see what the stream of bytes look like before we start decoding, here’s what our text looks like as a stream of bytes:

01101000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111 11100100 10111000 10001101

Let’s try to parse these bytes.

P.S, we’ll use this tool, to put in the decimal equivalent of our code point to translate from hex to it’s Character representation

The very first byte is 01101000, it starts with a 0, so it’s an individual code point, so we remove the first 0 and we’re left with 1101000, now this translates to U+0068 or decimal 104 which according to our tool translates to the letter ‘h’.

The second byte is 01100101, it starts with a 0, so it’s an individual code point, which translates to code point U+0065 or decimal 101 which is the letter ‘e’.

The third byte is 01101100, it starts with a 0, so it’s an individual code point, which translates to code point U+006C or decimal 108 which is the letter ‘l’.

The fourth byte is 01101100, it starts with a 0, so it’s an individual code point, which translates to code point U+006C or decimal 108 which is the letter ‘l’.

The fifth byte is 01101111, it starts with a 0, so it’s an individual code point, which translates to code point U+006F or decimal 111 which is the letter ‘o’.

The sixth byte is 11100100 and this is where this gets interesting, it starts with three 1s, so it tells us that this is part of a group of 3 bytes that need to be processed together, so we pick the next two bytes which form the group of 3 bytes that need to be processed together. Picking those 3 bytes we have :

11100100 10111000 10001101

We have our group of bytes that we need to extract our data from. Let’s remove the metadata that we used when we encoded our text, following our rule to extract data from each byte from the very first 0. Using our container analogy, this is what it’ll look like:

3 Byte Container

| Container 1 | Container 2 | Container 3 |

|---|---|---|

| xxxx0100 | xx111000 | xx001101 |

If we take the actual data bytes as shown above, we have this:

01001110 00001101

which if you take a look back seems similar to the binary representation of something, but let’s not spoil it, let’s follow due process. If we convert this binary, it translates to the hex value of 4E0D, code point (U+4E0D) and a decimal value of 19981. Now, using our online tool, we see that it translates to ‘不’.

VOILA !!!!!!!

We have successfully parsed our stream of bytes into text using Unicode and we can clearly see that we get our desired result as opposed to our previous approach of parsing individual bytes.

Hope this makes a little sense.

For some history into UTF-8 and other encodings, check here: